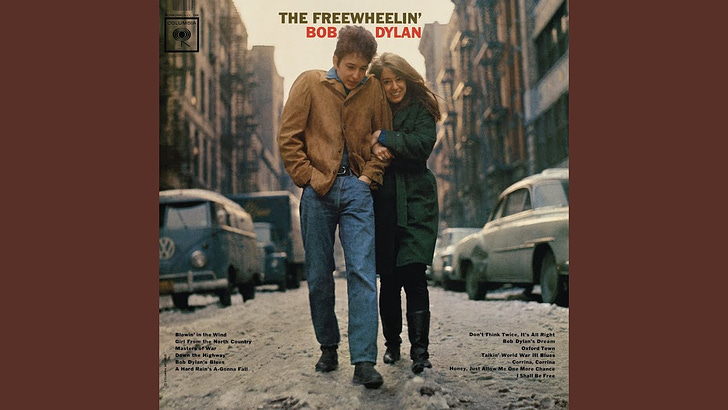

Tell It And Think It And Speak It And Breathe It

Bob Dylan: 'A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall' + being 14 + ugly basement remodels circa 1970

Dylan opens a door, and Leslie Carr (my mom!) walks through it. “That’s what I’ll do with my ideas, all of my ideas, as they come.”

I depend on income from writing and editing to pay my bills. Paid subscriptions — $5 (the cost of a beer or pastry!) per month, $50 per year — are what keep Tracks going. Consider upgrading. If you already have: thank you!

1970. I was 14 years old, in my parents’ basement, watching my father do his post-run stretches. The basement had just been “finished,” its dank gray cement covered up by a chaotic layer of poor taste incarnate. The walls were lacquered pine, busy with knots and gradations of color. The flooring was vinyl tile, mustard-yellow squares and marbled ivory squares set in a zigzag pattern. Fluorescent lighting, lots of it, beamed down onto upholstered plastic furniture that was sweaty in every season. The high counter was beige linoleum with chrome edging. The cabinets were pine with black hardware, too much of it.

My father’s stretching routine was unchanged from when that basement was dim and damp. But now he had a turntable up on the beige counter, and two of the cabinets were devoted to his record collection. He always had something spinning while he stretched, and I never knew what it would be. The Supremes, reminding me that you can’t hurry love? Harry Belafonte? Vivaldi? Judy Collins?

More often than not it was Bob Dylan. (“I don’t know what he’s singing about,” my dad said, “but I like listening.”) It was in that basement that I first heard “A Hard Rain’s a-Gonna Fall.” I was transfixed. My teenage preoccupations were everywhere in the song.

I saw ten thousand talkers whose tongues were all broken.

I was a severe stutterer, and when I heard that line I put my hands in grateful prayer position — thank you for mentioning us (kind of, sort of)!

I’ll tell it and think it and speak it and breathe it.

“Yes,” I said to my shy and powerless self. “That’s what I’ll do with my ideas, all of my ideas, as they come.”

But the song — the intensity, all the suffering — also frightened me. If a hard rain was gonna fall, what exactly would that entail? Would my father and I still be able to play badminton out back after dinner? Could I still live across the street from my friend Jeanne? Take the bus to the library? Or would there be troops coming over the hill? For a while I’d been reading my parents’ back issues of Time and my brother’s copies of the Village Voice: these shaped the questions in my head, but didn’t provide answers.

Who could I ask? My father was a perplexing mix of cool and clueless. My mother didn’t like to guess or interpret. She didn’t like me lolling about, listening to poetry. My brother was busy on his shortwave radio, eavesdropping on strangers in other countries, and he thought me ridiculous. My friends much preferred crooners or boppers to Dylan’s abrasive rasp.

I replayed the song again and again in the basement, long after my dad had gone upstairs. It continued to scare me, but for the first time I experienced fear and buoyant hope at the same time. The refrain — it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard, it’s a hard rain’s a-gonna fall — carried the promise of upheaval, but also of change and the relief change could bring. Maybe even justice.

Before “Hard Rain,” I’d thought — like most children — that things were the way they were and that the task was to learn about them. Institutions. Flavors of chewing gum. Kitchen appliances. Hair products. Religions, jobs, cultures. What people did with their basements. Listening to Dylan swung a door open, and on the other side there were new angles and new questions. Not just What? But also Why? and What if? They’ve been with me ever since. ✹

Such a moving in a evocative piece… Thank you!

Woah