Even Though I Wasn't Watching Twin Peaks, I Was Basically Living There

Julee Cruise: 'Falling' + Bucktown, Pennsylvania + Swiping tapes + Glimpses of Lynch

For Olivia Ciacci (aka ), Julee Cruise’s music from Twin Peaks perfectly evoked a beautiful landscape with violence rippling just below the surface. And she hadn’t even seen the show yet…

Jen was my neighbor, the one neighbor who was my age, and she was The Singer. She sang songs at school events and practiced on her back porch with an actual microphone. Her big numbers were “Kokomo” and “Wind Beneath My Wings,” which she sang at an assembly for Desert Storm, wearing a combat jacket.

She had two sisters, one older and one younger. I had two younger brothers, and one went to my middle school. On mornings before school, he and I would wait together at the end of Jen’s driveway for the school bus. Jen and her older sister would be there too, dressed in coordinated outfits: cute little white sneakers, capri leggings, tunic-length T-shirts, scrunchies. (When their younger sister was with them, they looked like the three Tanner sisters from Full House.) Their mom had taught them how to do their bangs so that the top half curled back in a poof and the bottom half curled forward over the forehead. Sometimes Jen sang while we waited, not quite full-volume, gesturing with her hands and staring off at the vista of houses on the other side of the road.

My brother and I, by contrast, were usually barely awake. Nobody helped with our hair or clothes. Half the time, people mistook me for a boy, because I looked like a young Leonardo DiCaprio. Most mornings, I was the one who woke my brother up, and on absolutely no mornings did either of us sing.

Jen and I weren’t best friends. But we were friends. When I was six, my parents had bought the plot of land next to her family’s house in Bucktown, Pennsylvania and built our house there. The road didn’t even have a name then. It was just RD4. Road 4. Soon after we moved in, my father got spooked by the sight of Jen and her older sister, identically dressed, standing silently at the end of our yard. They were quiet kids compared to my brothers and me, but Jen and I bonded over sewing clothes for our dolls and having pets that made lots of babies (She had mice; I had rabbits; we both had hamsters.) Later on, we helped each other nurse our unrequited crushes on boys. Jen read Lurlene McDaniel books; I read C.S. Lewis and Jane Yolen. We both read “The Babysitter’s Club.”

But only one of us had long hair with curled bangs, and only one of us could sing.

One day, we were balancing along the rock wall that ran the border of our backyards when I fished a cassette tape out of my jacket pocket and said, Hey check this out. My dad gave it to me and it’s amazing. Maybe you can sing one of the songs?

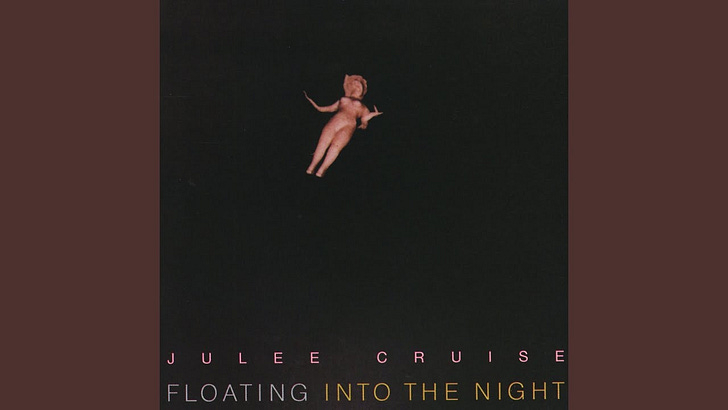

It was Falling Into The Night, the Julee Cruise album that featured her contributions to the Twin Peaks soundtrack. (All of the songs, not just those from the show, had lyrics written by David Lynch and music composed by his frequent collaborator Angelo Badalementi.) My dad had not given it to me. Possibly he’d said I could borrow it. More likely, I had swiped it from his car's tape deck.

Don’t take this as some testament to my advanced taste. Back then, I knew Nirvana was cool, and I wanted a boyfriend like the singer from Weezer, but I listened mostly to Top 40 crap I recorded from the radio onto blank tapes (or old ones that Dad said he was done with). I liked to talk into the tiny microphone jack on my boombox and record myself introducing the songs like a DJ. (“Next up, here’s Ace of Base with a song about wanting BABIES!”) But the Twin Peaks tape was sacred; I left it alone. Whenever I listened to one song, I had to listen to them all. My favorites were “Falling” (the song from the Twin Peaks opening credits) and “Nightingale.” The whole could not be broken, except for when I put the tape on at bedtime and fell asleep before the end of side A.

I had no idea what I was listening to. I was in eighth grade. I’d never even really seen Twin Peaks (which had aired three years prior), just caught glimpses of taped episodes my parents watched in their bedroom. I was obsessed with this story I didn’t know, a story for adults—smart adults—and the music felt like a way in. Beyond the synth-heavy music, which constantly teetered on the line between calm and unsettling, and Cruise’s breathy vocals, all I had were disconnected images. A small man in a red suit on a floor with zigzagged black and white tiles. Men singing and dancing in a cedar-lined office. A dead girl in a body bag. A picture of that girl from when she’d been alive, wearing a crown that rested on hair poofed up a bit, a thin fringe of her bangs curled forward over her forehead.

Bucktown could be beautiful: any place with rolling hills and lots of trees can be beautiful. But it was also dangerous. Most roads had a single yellow line down the center, just like the one I lived on, and just like the one in the Twin Peaks opening sequence. No sidewalks. If you wanted to go somewhere and didn’t have a driver’s license, good luck. Not that there was really anywhere to go: the main social hub was the intersection of Routes 100 and 23, which had a gas station on one corner and a bank opposite. On Friday nights, guys in flannel shirts, dirty jeans, and boots hung out at the gas station, got drunk, and tipped cows. “Preppy” or “European” sports were suspect, and only for guys: some girls and I had to join middle school boys’ soccer before the district would consider funding a separate team. When my brother got a spot on the brand-new lacrosse team, a bigger teammate who usually played football gave him multiple concussions, and nobody blinked an eye. When I asked my history teacher why there weren’t any women in our textbook, he got upset. With me. Go to the library! he said. There was spit flying. So I went to the library and read about Sojourner Truth and the Seneca Falls Convention.

Feminazi! snarked some guys who I was always trying to impress. Soon people started laughing at my clothes and looks. I had to plan my routes between classes to avoid running into people who would mock or taunt me. That was the culture: violence rippling just beneath a seemingly calm, arboreal surface. To add just a dash of fun, my mother decided we weren’t Catholic anymore and started making me attend a Baptist youth group. Suddenly, there were demons and hellfire all around me. No wonder the tape I swiped from my dad’s car felt like such a fit for my life. Even though I wasn’t watching Twin Peaks, I was basically living there.

One morning, Jen returned the tape at the bus stop, politely handing it over in a way obviously meant to communicate that there was no way she ever would have sung any of its songs. Soon we drifted apart. Jen didn’t play soccer on the boys’ team and didn’t get called a Feminazi. She kept singing and became a star of the school chorus and musicals. She marched in the marching band and had a boyfriend and made plans to study music in college. We lost touch, and I came to think of her as having existed on a different plane of Bucktown than the one where I spent my adolescence: a plane where being a talented, pretty singer made things easier. Years later, when I finally watched Twin Peaks—and learned that the pretty, put-together popular girl with poofed bangs gets brutally murdered, sucked under by the town’s current of evil—I thought of Jen, and realized that she had been living in Twin Peaks too. ✹

I know this intersection-- of Pa routes 23 and 100. But exactly.