Life's Thumbs In Our Wet Clay

Paul Lisicky on Joni Mitchell's 'Amelia' + Sticky Confusion + Touching Darkness and Living

In the just-released Song So Wild and Blue: A Life with the Music of Joni Mitchell, Paul Lisicky explores his decades-long connection to one of the great musical artists of the 20th century.

In this excerpt, he describes falling for Amelia,’ a song that sees Mitchell running from old strengths and exploring life in the ever-present shadow of loss.

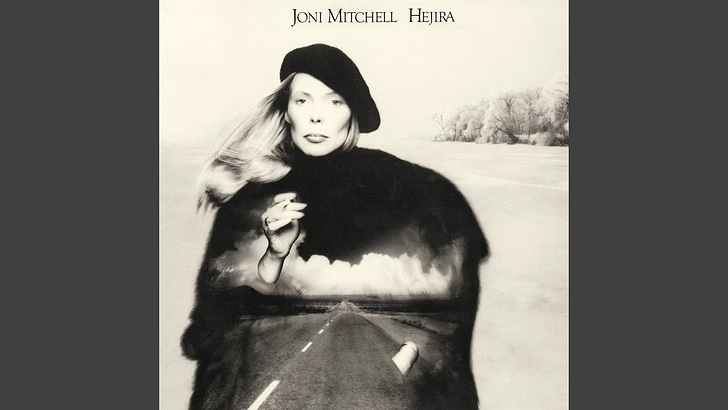

When I first listened to the album Hejira, I was confused by so much: its static melodies, the indifference to unexpected harmonic shifts. Joni’s wide-open chords still held the songs together, as did her words—which seemed to take precedence over the music. But Joni wasn’t making full use of the style she’d been developing over the years. There were none of the vivid colors of her two previous albums, none of the multitrack choral parts that always conjured up brain waves for me. She seemed to be rejecting the possibility of the wider audience she’d cultivated for her work. No Top 40 songs were going to come from this material, even if “Coyote” was released as the lead single. She was robbing herself of her strengths in order to concentrate on territory she hadn’t explored before—in this case, a consistently lower vocal register. Cooler atmospheres. A black-and-white movie at a time when color was the default.

But the music wouldn’t let me go. If I wasn’t actively listening to it, I was singing the songs in my imagination, in the car, or lying awake in the middle of the night. I wanted to get to the other side of bewilderment, which I experienced as an impediment: otherworldly rubble in the center of the road. I didn’t know that bewilderment was just what the work wanted of me, and one day the songs would open themselves to me like a person I’d misread, somebody I’d mistaken as shut down when there was so much life inside.

I should have guessed that “Amelia” would be the entry point. What other song felt so deeply emotional, in an extended way, without ever making me cry? Crying, I suppose, came about from disruption. A song or poem touched something you hadn’t seen coming, and it set you off, it broke you in two. “Amelia,” on the other hand, was consistently astral, even when it was back to Earth at the end, at the desert-bound Cactus Tree Motel. It was baked in an atmosphere that was sad, ineffably so, but the song was oddly hopeful too, though it didn’t declare itself as such. The speaker had touched something dark, but she lived. She survived—is surviving, unlike Icarus, who plunges to his death in the song. She was probably going to touch something dark again. She went forward with that but wasn’t demolished by that knowledge, unlike the reachers of Greek myth.

How did she make you feel it? Maybe it was the trick of orienting you in one key, F, and lifting you up into another, G. When I sat down to listen to the song fully, I took away three chords. I knew there were extra notes in those three chords, but they didn’t sound like the chords in Court and Spark and Hissing. For all of its allusions to flight, the melody limited itself to a six-note range, which was startling given the sublime range of “Car on a Hill” just two and a half years before. But the song was wily and a little secretive about that strategy. Maybe because the song was less about Amelia Earhart, whose desire to be the first woman in solo flight disappeared her, than it was about Joni, who lives. At this point in time, she was more interested in thinking about all the ways we were alone, all the ways we traveled with and developed psychic resilience through our losses.

And there she was at nine, airlifted from North Battleford to the polio clinic in Saskatoon. Far from home and friends, from parents. One hundred thirty miles away. Would she live? She couldn’t even move if she had the energy to. Not even allowed to look down at the farms that passed beneath her as the engine drowned out her voice.

But there was more. Maybe she was processing the tension between expectation and the inevitable outcome, which is another way to say that life makes a mess of our attempts to corral and shape it. Life chastens our reaching, whether it comes to love or the songs we write. Even when disaster has been averted, life is pressing its thumbs into the wet clay of our stories, reshaping the narratives we live by even when we don’t consciously think of them as narratives. Sometimes life leaves them in pieces: picture postcard charms. Individual moments in time, disconnected from one another, without emotional logic or causality. A pot dropped to the floor. Shatter.

Could I make meaning of any of that when it was all I could do to worry songs into being in the middle of the night? Whenever I tried to write like Joni, it sounded at best like an outtake. Descriptions and guitar chords untested by life experience. I knew the route before I set out to explore. Before I could lose—and fail at—something, I needed to do something first. I needed to love someone, needed to lose myself, and I was behind on that, way behind, while everyone else seemed to know that there wasn’t very much time. They made choices even though they might have known that they were the wrong choices. What would my love be? A person? A place? My music? To listen to this song was to listen to the life ahead of me—my death too. To mourn everything first—lost relationships, lost parents, lost places—as a way to prepare for my arrival. ✹

This brilliant piece has sold me on the book. It gets to so much of what I’ve learned from Joni’s music, and from song more generally.