In which, by chance, I discover Paul Simon’s ode to political dreams and schemes during the heady days of Occupy Wall Street.

Paid subscriptions — $5 per month, $50 per year — are what keep Tracks going. Consider upgrading. If you already have: thank you!

In the fall and winter of 2011 I spent many of my evenings hanging around the Wilmington, North Carolina offshoot of Occupy Wall Street. In the beginning there were nightly meetings at Greenfield Lake Park, where signs warned us not to tease or feed the alligators. People gathered under a pavilion and talked about how money was swallowing politics, about how we felt capitalism chipping away at our lives, about shitty health insurance. For a brief while there was a round-the-clock encampment in front of City Hall. I would often stay late into the night, chatting with whoever stopped by, making new friends (of a kind, anyway), telling stories and laughing together whenever we got heckled.

I never made up my mind to what extent I was there to participate and to what extent I was there to soak up the atmosphere so I could write about it later.1 But I enjoyed myself. Before, almost everyone I’d known in Wilmington had been from my graduate creative writing program at the local University of North Carolina campus. At Occupy I met new people and had different conversations than the ones I had with classmates. I liked hearing people say what they hated about how American life is structured, and I liked hearing them say it directly, without much protective irony, fumbling earnestly for the right words.

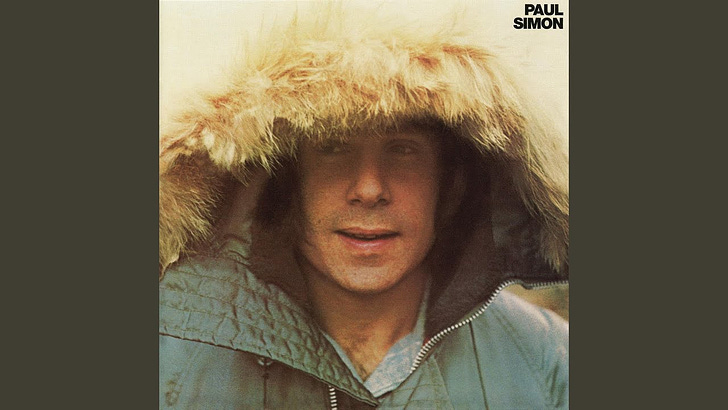

Sometime during this era I got a CD of Paul Simon’s 1972 self-titled album from the college library and heard (or noticed) “Peace Like a River” for the first time. I’d been listening to Paul Simon since childhood; I don’t think any other artist got more play in my mom’s Toyota Previa. But the only full Simon albums she had on rotation were Graceland and Rhythm of the Saints. Beyond that it was individual tracks she’d put on her own mixes: “Mother and Child Reunion,” “Train in the Distance,” “Hearts and Bones,” “Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard.” A bunch of the songs with Garfunkel, of course. But no “Peace Like a River.”

The song is a Simon anomaly. There’s a fair amount of politics in his oeuvre, but it’s typically (especially in his solo material) something his cosmopolitan narrators take in as observers, not an enterprise they feel much urgency about, and certainly not one they get involved in. In “The Boy in the Bubble,” when the narrator notes the era-defining rise of a loose affiliation of millionaires and billionaires, he’s almost certainly not describing something he approves of — but he doesn’t sound terribly upset.

“Peace Like a River” is different: it tells what is undeniably a story of political revolt, and it basically cheers the revolutionaries on, or at least sympathetically inhabits their perspective. The lyrics start from the perspective of a collective we that lives under the thumb of a repressive regime. There’s a curfew, but we stay up past it, making plans, trying to sort rumor from fact.

Ah, and I remember misinformation followed us like a plague

Nobody knew from time to time if the plans would change

There’s a sense of people getting excited and, simultaneously, trying to keep their excitement quiet. Simon sings over light acoustic guitar notes, backed by the soft drumming of a hand against either bongos or a guitar frame.

But then the restraint evaporates. In the closest thing the song has to a chorus — it appears only once — Simon’s voice gets buoyed by swelling choral aaaahs as he delivers lines that, in 1972, must have been unavoidable allusions to the Civil Rights movement:

You can beat us with wires

You can beat us with chains

You can run out your rules

But you know you can’t outrun the history train

The vocal revs up — I’ve seen a glorious day — then crescendos in a stretch of wordless keening: Aieee-eee-eeeee-eeeeeee! It sounds a bit like a celebration, a bit like a prayer.

After the climax the song comes down. The narrator is up in the middle of the night, too jittery to go back to sleep; there’s a possibility that the entire song to this point has been a dream.

During my Occupy era I, too, was often up late. Though I never spent the full night outside City Hall, I often lingered well past midnight. Sometimes I listened to “Peace Like a River” on the walk home, using it to amplify the encampment’s mood of improvised, conspiratorial struggle. In my apartment I might stay up even later, watching livestream footage and reading online dispatches from other Occupy encampments around the country.

Back then lots of people confidently opined that Occupy wasn’t accomplishing anything. It’s still a common opinion. I think it’s wrong, not just because of all the real-world initiatives that grew out of Occupy and improved people’s lives, and not just because of how it intertwined with other currents in politics, culminating in (among other developments) the Bernie Sanders presidential campaigns. There’s also the experience itself, which persists as a reference point not just for its participants but also for the thousands who followed their story online, or who’ve looked back on it in retrospect. Whatever else, it was practice at looking off in the distance together, scanning the horizon for the outlines of a better world.

Almost 13 years later, “Peace Like a River” helps remind me of the path I walked from City Hall to home — but also that Occupy was itself a performance of an old (and glorious) melody, one that’s always being taken up by new singers, adding new words as they go. Aieee-eee-eeeee-eeeeeee! ✹

Also:

Besides this one, Tracks on Tracks has published two pieces so far: I wrote about Belle and Sebastian and moving on and staying put; Becca Rothfeld wrote about The Magnetic Fields, teen yearning, and nostalgia for the past she once longed to escape.

I mentioned Tracks in an interview with the New York Review of Books.

On deck:

Screamo in suburban LA.

“Farewell Transmission” en route to a breakup.

Crying at the movies with Nina Simone.

And … more!

I did write about it later.